I go behind the scenes at Air Salvage International: “I’m not just a scrap man!”

Links on Head for Points may support the site by paying a commission. See here for all partner links.

With its rolling hills and golden villages, the Cotswolds is the last place you’d expect to find an airplane salvage yard; let alone the biggest privately owned dismantling company in the world.

Yet here it is, tucked away on the fringes of the Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is just five minutes from the small village of Kemble and just over an hour from Paddington Station.

Since 2000, Air Salvage International has called the Cotswolds its home. In that time it has grown to become the largest tenant at Cotswold Airport, a small ex-RAF airfield that is now home to several flying clubs, pilot training schools and light industry.

Part of the appeal is the 2,009-metre long paved runway – long enough that even the largest passenger aircraft, including the Boeing 747, can land here.

This makes it the ideal location to set up a airplane scrapyard, although as founder and CEO Mark Gregory says, there’s a lot more than to ASI than just scrapping old aircraft.

Through a variety of subsidiaries including aircraft maintenance (GCAM), parts trading (Skyline Aero), a parts repair facility (Southern Airframe) and a light aircraft flying (Cotswolds Aero), ASI now offers an end-to-end service. “People don’t realise what we get involved in.”

I’m on a tour of the facilities in Kemble on sweltering day in early September – the summer we never had – with a group from The Aviation Club UK, of which Mark has been a member for many years (as has HfP).

Mark is showing us around the two hangars his companies operate from, as well as the large open-air scrapyard and his own little pet project – an old Boeing 727 with a storied history that used to be used by the Kuwaiti royal family as a VIP jet.

Mark started his career working at Dan-Air and spent fifteen years as an engineer working on the Boeing 707, 727 and 737.

When the airline hit financial trouble in 1992 it was bought out by British Airways for £1. BA absorbed its operations, ditching the older aircraft but retaining the newer 737 fleet to form its core shorthaul operations at Gatwick.

Mark was made redundant and started dabbling in light aircraft “although there’s no money in light aircraft at all.”

Using his redundancy pay, Mark bought an old Hawker Siddeley HS 748 which he planned to break up for spares. Janes Aviation / Emerald Airlines had just bought the remaining Dan-Air 748s which he knew were in need of parts. Mark never looked back.

Initially, this new job took Mark to where the aircraft were, and in Exeter he met Philip Meeson, owner of Jet2 and the Dart Group. “Philip looked at me with my long hair and said something I’m not going to repeat!” But he entrusted Mark with his fleet of Handley Page Dart Herald and later the A300 – the original Airbus widebody, and a big step up from the smaller jets Mark had worked on until then.

Philip introduced him to Virgin Atlantic, which at the time was operating a fleet of Boeing 747-200s. Around 2000, Virgin decided to use some of the older aircraft to feed parts to their new aircraft. Knowing the potential for bad publicity, they insisted it had to be done off the radar and not at Bournemouth Airport, as originally suggested.

Mark then discovered Cotswold Airport. It ticked all the boxes: it was out of the way, had a a ‘proper’ runway and plenty of space for salvage operations.

Air Salvage International promptly moved in, and now aims to disassemble 40-50 aircraft on site every year. The past two years, affected by covid, saw demand reduce with 20-35 planes taken apart.

Customers now include British Airways, Delta, Lufthansa, Jet2 and many others. ASI got its moment in the sun when British Airways flew in 19 of its 34 Boeing 747s to the airport for storage and eventually scrappage.

Two still remain: one owned by Cotswold Airport itself and now an events venue offering regular tours, whilst the other sits in ASI’s salvage yard waiting to be scrapped.

ASI’s engineers travel all over the world to scrap aircraft that are no longer air-worthy, often to out-of-the-way airports such as, for example, Togo.

These days, most aircraft scrapped here (about 90%) are taken apart before their end-of-life date. After all, the aircraft are perfectly airworthy, having flown themselves in.

Often, however, the value of the parts in the aircraft is worth more than the entire aircraft as a whole. The engines alone can often fetch a higher value than you would get for the whole plane, so it makes sense to sell those off and any other valuable bits (mostly the mechanical parts) before scrapping the remainder.

Other valuable parts include the auxiliary power unit, landing gear, avionics, instrumentation and fuel systems, all of which can be refurbished and resold.

In total, about 98% of current generation aircraft can be recycled, and none goes to landfill. The remaining 2%, mostly insulation and carpet, is incinerated and the resulting ash is used in road fill.

Once all the valuable pieces have been removed, a Boeing 737 takes about two hours to dispose of, turning into approximately 30 tons of metal. A Boeing 747 takes longer at two days and yields around 120 tons of crushed aluminium, which goes for recycling.

Next-generation aircraft pose a challenge, however. There are no cost-effective methods of recycling the carbon fibre composites that modern aircraft such as the Boeing 787 and Airbus A350 are largely made of. Whilst various start-ups are trying to find ways of reusing these materials, none have cracked it so far. The cost to recycle is higher than the materials are worth.

Sometimes, however, parts of the aircraft are sold whole. The SAS training facilities in Herefordshire have a static 747 and two 737s which they use for training, whilst a tail of a 737 is part of the Swarm roller-coaster at Thorpe Park. Even the Home Office is getting in on the action, with a couple of fuselage cuts it will use for training staff for deportation flights.

It’s not uncommon for film crews to rock up at Cotswold Airport, either. ASI’s aircraft have been used for productions such as Batman, Star Wars, Mission Impossible and Fast and the Furious as well as a range of UK TV shows such as the upcoming season of McDonald & Dodds on ITV.

During covid, there was a frenzy for parts from enthusiasts wanting to get their hands on Boeing 747 memorabilia. You may remember my article about it in The Times.

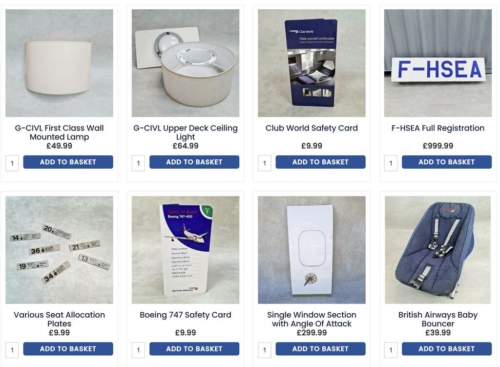

“We were getting a little bit fed up of the constant emails to buy parts,” Mark says, so they decided to set up a dedicated website where ASI’s engineers can list interesting items for sale (screenshot below). Any proceeds pay for the work Christmas parties, which last year took all the staff and their families to a hotel for the night.

Throughout the years, ASI has been tasked with a number of high profile projects, including the disassembly of two British Airways Concordes. One went to Brooklands Museum in Surrey and the other to the National Museum of Flight in Scotland.

They once found £4 million-worth of cocaine on an old aircraft from Colombia. “Why do you think I have so many classic cars?” jokes Mark.

Things have been a bit quieter since the pandemic, when covid grounded entire fleets of aircraft and wiped out the need for spare parts. 747s – many of which still fly for cargo – were one of the few exceptions. As numbers of in-service aircraft increase, so too should the demand for parts.

Since its founding, Air Salvage International has dismantled over 1,000 aircraft and Mark shows no signs of retiring. Last year ASI celebrated its 25th anniversary. It remains privately owned and Mark is still hands on. “It’s almost turned into a bit of a hobby to come into work.”

Comments (42)