Why the disappearance of First Class is down to bad marketing, not lack of demand (Part 2)

Links on Head for Points may support the site by paying a commission. See here for all partner links.

This is Part 2 of a two-part guest post by Oliver Ranson, who runs the fascinating Airline Revenue Economics blog on Substack (free to subscribe, click ‘Let me read it first’ to skip the sign-up page).

He published this article a few weeks ago and we thought it was worth sharing. You can read Oliver’s previous HfP article, “How we built the first business case for the award-winning Qatar Airways Qsuite“, here.

You can sign up to receive Oliver’s future articles by email here. There is no charge. Don’t carry on reading until you’ve read Part 1 of this article which is here.

First Class microeconomics covers nine revenue generators

Given the underlying demand for First Class that must exist, given macroeconomic conditions, there are nine pathways to revenue generation for airlines.

1. Higher fares: This one is obvious – some passengers are willing to pay more than the business fare and the price gap to private aviation is high. Offering First causes some passengers to voluntarily pay more for their flights.

2. Economy removal: Selling economy seats is easy – you just reduce the fares. Human nature being what it is, the more economy seats there are the more pressure there will be on revenue management to lower bid prices. Unfortunately this approach is not profitable. Offering First removes a natural distraction for an airline’s sales team and allows them to concentrate on more valuable opportunities, boosting revenue across all cabins.

3. Whole network value: Offering First on a limited selection of flights is a common strategy. Qatar Airways operates First Class to a few destinations on A380 super jumbos (see my Substack article) but they only have a few of these.

This approach may produce less revenue than not offering First at all because of passengers wishing to connect and the airline completely losing regular First travellers who ‘always’ fly at the front. Having First Class seats going unsold (or spoiled as we say in the trade) because a passenger wants to travel first all the way or all the time and uses competitors instead harms revenue.

4. Alliance ‘circle’ fares: Each airline alliance has members with First seats and they all offer ‘circle’ fares, like round the world or multi-continent tickets. If one member does not then they may be reducing the value of their alliance membership, which is not cost-free for airlines.

5. The “halo” effect: If something costs $10,000 it must be good and the things associated with it must be great too. That argument appeals to the primitive part of our brains and it works for airlines too.

If passengers see that an airline offers a great First Class, they might be more inclined to buy tickets in other cabins expecting that they will be good too. The result is extra demand and revenue in all cabins, not just First, and a potential boost to the airline’s commercial marketplace products (see my Substack article here). When Etihad was running primetime TV advertising with Nicole Kidman for its ‘The Residence’ A380 ‘apartment’, it wasn’t ‘The Residence’ that it hoped to sell.

6. CEO choice: If a CEO flies an airline in First and likes the service a lot, that airline may be well-positioned to sign a corporate contract for a thousand business or premium economy (see this article of mine here and this article here) seats, which is where they really make their money.

7. Loyalty and upgrades: Some passengers may fly an airline or use a co-branded credit card more often if it enables them to earn the mileage for a “once-in-a-lifetime” redemption worthy of a special occasion. First is more charismatic than business, compounding the impact. Other passengers may be keen on using miles or money to upgrade (see this Substack article and this article), including when their employer pays for business. These effects boost demand and revenue for both business and First Class.

8. Mileage liability: Airlines must account for mileage currency as a liability. The more passengers there are who use large stacks of points for First Class redemptions, the lower the liabilities become. A small effect perhaps, but still relevant.

9. Multiplier effect: All the above may have “multiplier effects”, for example higher seat sales and higher yields together increase revenue by more than the sum of each.

How to market First Class

The prosperous do not seem to trade down when it comes to other products and services – I do not see why they would they do so in air travel?

First Class was worthwhile for airlines in the 1990s, when there were fewer millionaires, lower stock market returns and fewer successful businesses, and the product was not as good as it is today (see this Substack article) – I do not see why it should not be so today.

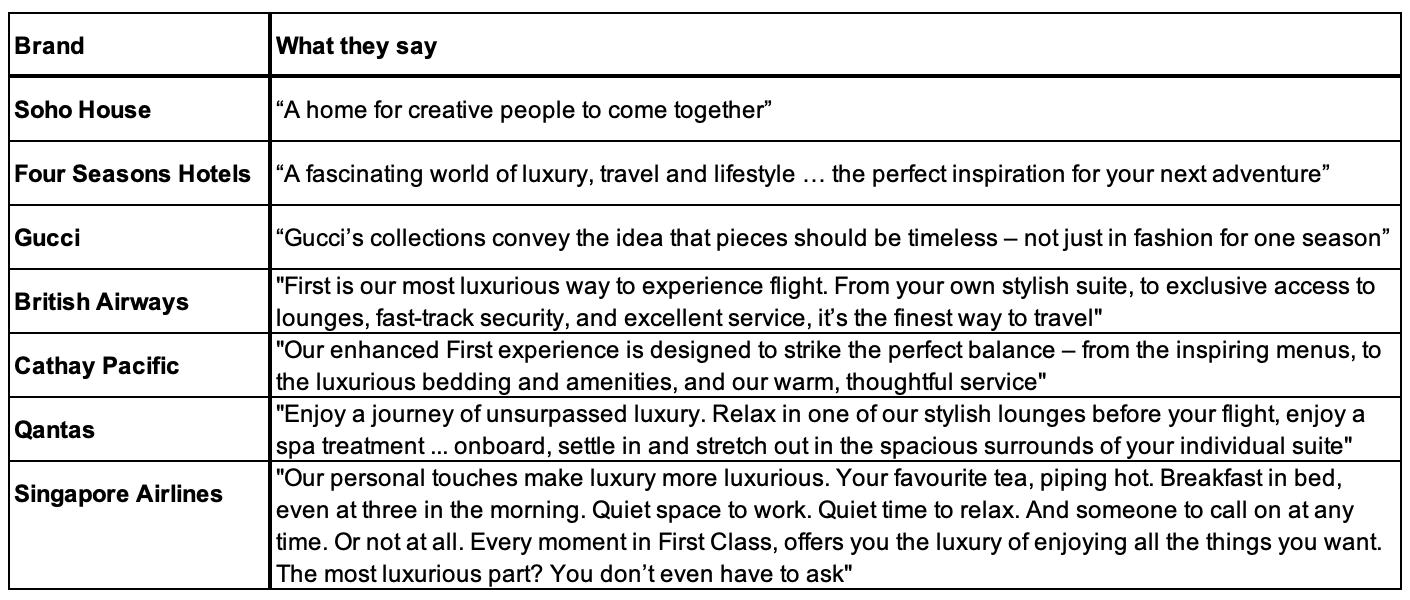

Taking a look at the marketing data in the table below, it looks like airlines are doing a poor job of marketing the front cabin.

What strikes me about this table is how the three luxury non-airline brands are much more aspirational and philosophical in their language. They are selling a lifestyle (benefits) rather than a product (features).

Although the airlines’ language is flowery it is much more matter of fact – suites, lounges, menus, bedding, spas, all features not benefits which any sales pro will tell you is a mistake. I believe that if airlines marketed their First Class as a lifestyle brand that also happens to be a time machine (see above) they would be much more successful.

Successful First Class pricing can be counter-intuitive

The rule of thumb I follow for inter-cabin upgrade pricing is that each step roughly doubles the fare received by the airline, although not necessarily the sticker fare. So for example an airline might receive £500 for economy, £1,000 for premium economy, £2,000 for business and £4,000 for First.

But many business class passengers do not pay the sticker fare – the buyer gets a discount either at the time of purchase or at the end of the year. This might be because their employer has a contract with the airline but there are also some wealthy families in cities like Hong Kong who are known to have deals too. When passengers travel in a group or on an inclusive tour there might not even be a sticker price.

Such discounts are rarer in First as the smaller cabin does not facilitate the volumes required for the airline to take an interest. Corporate policies limit discounts up-front too and while a CXO might travel in First at their contract rate most managers will only be allowed to fly business. Significant discounting in business class has some surprising implications for successful pricing in First.

First Class sticker fares can be cheaper than business:

Set business class fares at £5,000 and First Class fares at £4,000 – if the expected discount is 50% in business and 0% in First the airline will receive £2,500 for business and £4,000 for First, which is about right given the difference in the seats. This strategy works well if business class demand to come (see this Substack article) is high.

Sell First by inflating business prices:

Set business class fares at £3,800 and First Class fares at £4,000. Many passengers who will buy a business class ticket anyway but have some control over their travel (successful small business owners for example) will pay the extra £200 for First, think they got a great deal and be more likely to travel in the highest cabin in the future, boosting lifetime value.

This strategy works well when business class demand to come is low but travellers own their budgets and willingness to pay is high. It might also work well with passengers redeeming miles on some routes.

Offer special First Class fares to smaller businesses rather than larger ones:

Many airlines have a scheme for small businesses – when I was at Qatar Airways we had Qbiz. Nowadays my company is a member of On Business, the American Airlines, BA and Iberia programme. Corporate customers may have contracts and high travel budgets, but their travellers are not buyers.

At a small business on the other hand the decision-maker may be the traveller. It makes sense for airlines to offer First Class as a treat to SME customers – “enjoy the fruits of your success” or a similar tagline would work well – and the SME programme is the perfect channel to make this happen.

Bundle First Class with ticket flexibility

Sometimes a business class ticket that upgrades to First Class for free is a compelling reason to fly on an airline, even if another is cheaper. The reason is that business travellers can expense the business class fare to a customer, who never actually sees that the traveller actually flew in First.

British Airways used to do this a lot. The catch was that you needed to buy a relatively expensive ticket with flexible conditions for change and refund. This approach is great for airlines because it gets people to voluntarily pay more, even if a cheaper fare is available.

If you sell First Class seats or any other cabin product, or if you are an airline wanting to make your First Class more successful, reach out to me to help you achieve your goals – oliver AT ransonpricing DOT com

Comments (82)